American Ale Sparkles With a British Accent

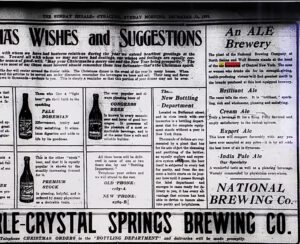

This impressive spread of beers, advertised in 1903 in Syracuse, New York, includes numerous North American ale types I’ve been discussing.

It’s a contemporary, eclectic beer range offered under one roof as National Brewing by this time was wholly-owned by Haberle-Crystal Springs, lager brewers.

(For background on Syracuse brewing in this period see the multi-authored The History of Beer Brewing in Syracuse, ed., Dennis Connors, Onondaga Historical Association).

As I mentioned recently, in 1935 The American Brewer published an article on cream/lively ale and sparkling/present use ale as understood before Prohibition. Summarizing the presentations of the veteran North American brewers, the two classes can be explained as follows.

Sparkling/present use was:

i) originally based on “matured” (stored, stocked) ale; the cream/lively type was all new beer;

ii) chilled at some point after fermentation; cream/lively ale initially did not benefit from mechanical refrigeration; and

iii) made brilliant from chilling and filtering; cream/lively ales were not crystal clear.

A good explanation of cream/lively beer can be gained from an 1897 article by U.K. brewing scientist Horace Brown, here. While he uses the term present-use as well, it is clear he is referring to the older cream/lively group. This is emphasized by his statement that the beers rarely poured very clear and also he makes no reference to stock ale as a base for the beer.

As I mentioned previously, a steam beer commentator c. 1900 stated steam beer, the bottom-fermenting counterpart to cream/lively ale, also came none too clear. This trait among others was shared by cream ale and steam beer.

Wahl & Henius’s 1902 explanation of cream and sparkling ales in their textbook on American brewing is broadly consistent with the 1935 article, with an important exception. They do not refer to matured ale being the basis of sparkling ale. I think the reason is, they were based in Chicago and surrounded mainly by lager brewers. The finer points of cream ale brewing likely were not present to their mind or even known.

As well, and this is reflected in the 1935 discussion, practice had evolved prior to Prohibition. Some brewers were marketing a sparkling/present use ale that was not a previously matured ale, although it would generally be subjected to some cold treatment before dispatch from brewery.

See Henry Sturm’s and Eric Wollesen’s remarks in particular in the article. But things did not start that way:*

It is evident that finally the various categories merged, but not in the period we are discussing.

India Pale Ale, for its part, before WW I was mostly still a strong (6-7% abv), bottle-conditioned specialty. Cream and sparkling ales were less strong, 5%-6% abv by my canvasses, steam beer ditto.

Allsopp Enters the Picture

A second news article, in the Syracuse Journal in 1901, explains that National Brewing had adopted the Allsopp Brewery brilliant ale system.

Allsopp, the great Burton brewer was famous for its Red Hand I.P.A. By 1900 it was also marketing a “dinner ale”. This was a lower gravity bottled beer, an evolution of AK and similar light bitter ales, rendered brilliant for table use.

Other UK brewers about this time were marketing brilliant, gem, diamond, and similarly termed ales. These were meant for quick consumption and did not manifest the characteristic flavours of beer long-matured in cask and bottle. Their storage was much abbreviated, versus the classic I.P.A. and old ales.

Allsopp is well known in brewing history for having moved into lager-brewing early. In 1899 it built an impressive lager plant in Burton, as Ian Webster records in his 2015 history of Allsopp and Ind Coope (they merged in 1934).

Webster explains that 26 Pfaudler enamelled glass-lined steel tanks were brought from Rochester, NY for this purpose. Allsopp was deploying, in part at least, an American approach to brewing lager.

Rochester, NY is just down the road more or less from Syracuse.

How odd then, or perhaps it isn’t, that the influence came back the other way. The Empire State assisted Allsopp to brew lager, and Staffordshire returned the favour with its brilliant ale method.

The 1935 article states that a brewery in New Jersey, not identified but probably we think Ballantine Brewery, devised brilliant, aka sparkling, ale. How and where it got the idea from is unknown, but perhaps National/Haberle felt it was best to go to the source of ale-brewing, Britain, for best methods. Haberle likely knew of the Pfaudler deal through trade connections.

It is interesting that in this very period Ballantine is advertising its India Pale Ale as without the “clouds” of “imported ales”. See for example this squib ad in 1900 in the New York Evening Post.

As to what the National and Allsopp brilliant ale method was, the 1901 article states that National had installed the same type of steel conditioning tanks Allsopp had bought for its lager plant. In fact, a Mr. White came from England to help with the work. This suggests that the brilliant ale was cold-aged in those tanks, as lager was in Burton for Allsopp, but was not itself a lager.

I suspect as well that the base pale ale for both brilliant ales, whether aged before or during conditioning, was aged longer than for cream ale but not as long as for India Pale Ale. Contemporary commentary in the UK stated the newer class of light bitter ales received less maturation before dispatch to market than stock ales such as I.P.A.

Frank Thatcher’s prescribed two to four weeks for this class of beers, but viz. Allsop and National specifically, one can only speculate.

National sold both cream and brilliant ales, indeed also an export, apart its I.P.A. These classes likely were aged for different periods before being sent to market in cask or bottle. Cream ale was likely at the low end, a week or so (see Wahl & Henius), then brilliant ale, maybe a month or two, then export ale, maybe a few months, then I.P.A., maybe nine months to two years.

Allsopp Dinner Ale in the U.K.

Allsopp Light Dinner Ale was likely the model for National’s brilliant ale. Alamy has an advert here that seems of the period in question.

Mitch Steele, at pp. 76-77 of his text on IPA (2012), has Allsopp Burton Light Dinner ale in 1896 at 13.48 P., finishing 1.93 P., 5.81 abv. An article in the Journal of the Society of the Chemical Industry, in 1897 renders substantially the same results (alcohol there appears to be by weight).

Steele has Red Hand IPA in 1901 at 6.80 abv which could well go higher with further age. The difference in quality (from a market standpoint) is evident and the IPA commanded a higher price always in this period.

For storage time, see my comments above.

The Pfaudler equipment was not yet installed at Allsopp viz. the 1896 and 1897 Dinner Ale data. I suspect after the installation the tanks were also used to cold-store Dinner Ale, in other words that the Dinner Ale changed from a bottle-conditioned to a chilled, filtered, bright beer.

To my knowledge Allsopp, at least before 1934, never marketed a brilliant ale as such, so in 1901 this class must have been its Dinner Ale.

I doubt any form of Allsopp dinner ale, or National’s by extension, ever used lager krausen. I think it was cold-storage and filtering that joined them in character, and likely other attributes. Perhaps force carbonation or ale krausening, yeast type, hopping, two-row malt, a similar storage method and temperature, or a combination.

Ale vs. Lager Character in Brilliant Ale

The result of it was that the 1901 article claimed National’s brilliant ale retained an ale character, while competitors’ brilliant ale tasted more (it said) like lager. Indeed some American sparkling ale, Wahl & Henius implied in 1902, had a lager character due to use of lager krausen. Likely green flavours were meant such as dimethyl sulphide.

Bartels of Syracuse was likely one of the brilliant ale competitors alluded to in the 1901 article. Bartels marketed a brilliant ale in about the same period as National, Old Devonshire Brilliant Ale (ad linked is from 1909). The English reference is interesting, perhaps an implied riposte to Haberle viz. the character of its brilliant ale.

Finally, some readers may recall my post about a mini-keg of Allsopp ale available in New York State in approximately the same time. In light of the foregoing, it is pretty evident this was brilliant ale, probably Allsopp Dinner Ale despite being marketed as Allsopp Pale Ale. They didn’t say India pale ale.

See Part II to this study.

Note: the source of above image(s) is stated and linked in the text. All intellectual property therein belongs solely to the lawful owner, as applicable. Used for educational and research purposes. All feedback welcomed.

……………………………

*The quotation shows a practice not dissimilar to the old way of dispensing Guinness, or some porter in England, or some steam beer, as I discussed earlier. The same circle of practices comes round and round in widely dispersed contexts.

This is a comparison of data for two sparkling and a cream ale in 1908, from a Wahl Henius assay.

The alcohol, rendered in abw, averages about 5.7% abv.

Thanks for this. I live in Syracuse and our local beer history is something I need to spend more time digging into.

Thanks, the hyperlink given to the Onondaga Historical site study is a good place to start. It is well-illustrated as well, which adds to the value.

yeah, it was a great read. I’ll have to make an OHA trip to dig deeper when they re-open.

Thanks, and you probably I know I think of the Haberle-Congress lager recreations. I understand there are two, one sponsored by the OHA and a local brewpub, and another by descendants of the Haberle family. The latter have a website that mentions a lager and proposed release of further beers.

Gary

yeah, I’ve had quite a lot of the OHA-sponsored Congress … it’s definitely a modern interpretation, but still delicious.

The Haberle family one I’ve had a few times, and it’s always tasted like mediocre homebrew to me. The brewery that they were using declared bankruptcy a while back, so I’m not sure of its future.

Okay thanks for update, good to know.