It has been speculated that early distilleries in Manhattan made genever. This is the Dutch gin still consumed in its homeland albeit in a typically more neutral form than originally.

The Dutch or “Knickerbockers” as called by the English and Yankees settled what became known as Manhattan. England took over the island in 1664. Holland wrested control a dozen years later, but the English soon took it back. It stayed with the Crown until the American Revolution and Independence.

Still, Dutch cultural influence long-endured, in fact well into the 19th century. It may surprise some that a variant of the American Dutch vernaculars, Jersey Dutch, was spoken even into the 20th century.

The first distillery in Manhattan was opened by the notorious Willem Kieft in 1640. He was a merchant and governor of New Netherlands, the name of the new Dutch possession. He may have made genever, known in Holland since the late 1500s.

Various histories of early New York, and books on spirits, describe his product as genever, whiskey, or fruit brandy.

In Holland today a variety of genever types is made. Tristan Stephenson gives a succinct summary in his 2016 book The Curious Bartender’s Gin Palace. The more flavourful ones rely on a good dose of “maltwine” (moutwijn) as the heart. This is a cereal beer distillate brought off the still in the low range typical for genuine whisky. Indeed Stephenson’s outline of double distillation is very similar to the procedure used to make bourbon or rye whiskey today.

Wheat, rye, corn, and/or barley malt can be used for genever but rye figures in most mashes, often prominently. In some 19th century recipes rye alone is used with barley malt to make genever.

Juniper, the piney, purple berry of the forest, has always been a flavouring for Dutch gin. It was originally employed to mask the pungent flavours of new distillation and probably as a would-be medicament. Coriander and many other spices and flavourings were and are also used, but each producer had his style.

Originally the berries were ground with the grains and mashed fo their slight saccharine value. Later, the spirit was re-distilled with these flavourings to infuse their essence. Today, the latter method is used or alternatively, the flavourings are simply macerated in the finished spirit.

English gin derives from Dutch gin with two main differences. 19th century London distillers hit on a formula to use neutral spirit as the base, not a congeneric white spirit. This resulted in a cleaner style than for traditional genever.

Also, the flavourings in English gin have greater prominence than for traditional genever. The reason is simply that without the strong flavour of maltwine to inform the taste, the “botanicals” must provide that function. Hence, to blend and infuse assumes primary importance, and becomes the art for the English gin distiller.

Almost all genever today is blended but the better grades have a decent percentage of maltwine, it runs from a few percentage points to 51% ormore.

Anchor Distillery in Brooklyn, NY was a noted gin distillery between 1808 and 1819. It was owned by a scion of a famous family, Hezekiah Pierrepont – the surname was sometimes spelled Pierpont. The image below is via www.nypl.org:

Pierrepont bought the property in Brooklyn, apparently in 1808, from Philip Livingston, a signer of the Declaration of Independence. Livingston had operated the site according to various accounts as either a brewery or distillery. Older sources suggest, a brewery. It may have been both, or at different times.

The distillery was near a grain mill on the East River. Henry R. Stiles described the venture and special reputation the gin enjoyed in his 1869 A History of the City of Brooklyn:

Pierrepont’s Anchor gin distillery was on the site of the old Livingston brewery, at the foot of Joralemon’s lane. Mr. Pierrepont had rebuilt the old brewery building, a large wharf, a windmill, which was exclusively used for the purposes of the distillery, and several large wooden storehouses, in which he kept the gin stored for a full year after it was made, by which it acquired the mellowness for which it was peculiarly esteemed. The distillery was discontinued about 1819; was sold to Mr. Samuel Mitchell who used it as a candle factory for a time, and subsequently was occupied as a distillery by Messrs. Schenck & Rutherford; and having since been raised and enlarged is now (1869), occupied as a sugar house.

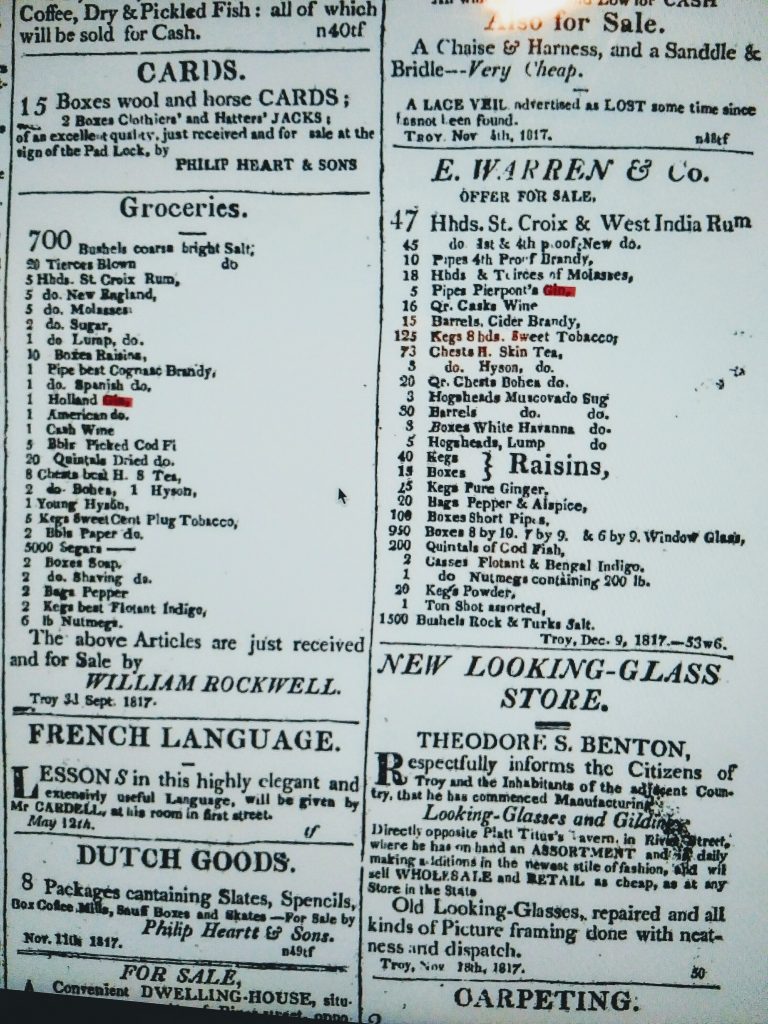

The first image above is from an 1818 issue of the Northern Budget, via NYS digitized newspapers. This newspaper was published in what is now Troy, NY, a city near Albany, up the Hudson from Manhattan.

Pierrepont gin is offered as part of E. Warren’s stock of goods. The merchant with ad juxtaposed to the immediate left sold both “American gin” and “Holland gin”, the original.

Troy was settled by Dutch colonists, with English-speakers arriving later. One ad still touts “Dutch goods” 154 years after the English first took Manhattan!

While four generations had lived in former Dutch New York from the English takeover until the heyday of Anchor Distillery, there is no reason to think Anchor Gin was anything other than a domestic take on Dutch gin. Via local distilleries such as (probably) Kieft’s and imports to New York from the mother land, genever would have been familiar to the citizens of New Netherlands.

True, New York’s population was heterogenous by 1800 and this was so even under Dutch rule, but it makes sense that tastes imparted by the first arrivals remained rooted.

Not that other residents in Manhattan wouldn’t have enjoyed genever. “Hollands”, as the English called it, was one of the first truly international spirits. The English and their possessions drank lot of it until late in the 1800s. Also, the English form of gin c. 1800 was still in gestation: all gin was Dutch in style and the only question for foreign types was one of fidelity.

Moreover the English had no whiskey tradition to joust with Hollands gin until Scotch whisky was well on the march. That only occurred much later in the 1800s.

There was of course rum on the eastern U.S. seaboard and no doubt many in Manhattan drank it, or brandy, but there was lots of room for the gin introduced likely by the first settlers.

Pierrepont’s product had cachet for being aged and similarly some modern genever receives a period of barrel aging – the Dutch connection all ties it together.

Period distilling manuals, e.g., by the Americans Harrison Hall and Samuel M’Harry, state rye whiskey was the base for American gin. What made it gin was addition of juniper berries, juniper oil, turpentine (felt to be similar to the piney smell and taste of juniper), and/or other flavourings, all as discussed by these authors.

Did Pierrepont make a rye whiskey to serve as the base of his gin, as advised by these contemporary writers? Yes he did. Here is the proof, from the 1962 enlarged and updated biography of the Pierrepont family, The Pierreponts, 1802-1962; the American forebears and the descendants of Hezekiah Beers Pierpont and Anna Maria Constable by Abbot Low Moffat.

A rye-and-corn spirit base makes sense given that Dutch maltwine, the heart of true genever, is precisely a cereal whiskey of which rye is an important element. Maize is frequently used as well today.

Did Pierrepont sell any of his whisky not ginned up, sell that is the rye schnapps of the German farmer-distillers in Pennsylvania? Perhaps, but I haven’t seen any evidence. Maybe the gin was so good no one wanted the rye spirit on its own, at any price.

Pierrepont’s gin was long-remembered in New York. Even in the 1880s, the Evening Post called it the “most celebrated American brand of gin” ever made.

And so one way to look at Pennsylvania rye is the frontier distillers were simply making a stripped-down gin. Maybe the juniper and other flavourings were hard to find in many areas, or viewed as dispensable in the rude conditions of frontier.

You might ask: how would German speakers deep in the new frontier, or unlettered Scots-Irish farmers, know about Dutch or even Manhattan gin?

Perhaps one answer is not to look at these traditions hermetically. Europe had a unified culture, and still does, from the Holy Roman Empire (at least) on. From art to literature to food to music and more vast areas of knowledge are common to countries or regions separated by long distances, borders, and languages.

Maybe grain and wine distillation across Europe was a common patrimony by 1700. Seeking precise national and ethnic demarcations to determine stylistic origins, in this light, may be unhelpful.

And another point. While scholarly studies have been written on the history of distillation and stills, how often has this history been linked to the spirits that became standardized in different places? Distillers’ business records might be quite revealing in this regard.

Does it not make sense that someone proposing to make a costly investment in a copper still and related equipment would ask the maker, what grains do you recommend for your apparatus? We can only get buckwheat and rye in our section of the state, can I use them in your tubs and stills? Should I malt everything? Have you heard of anyone adding burnt sugar to finished spirit?

Maybe those who supplied stills to frontier distillers also supplied them to Manhattan distilleries, and relayed some important information. It makes sense, eh?

To sum up: American moonshine whiskey and by extension bourbon, straight rye, and Canadian whisky may be first cousins with, or even the New World children of, Dutch gin, rather errant relations given the monastic and learned associations with gin’s origin. Difford’s Guide outlines some essential early history.

As with all whose lineage is tangled or dubious, surpassing success confers all necessary breeding. Today, bourbon and rye are gentry in the spirits world.

Note re images: the images above were sourced from the links mentioned in the text. All intellectual property therein or thereto belongs solely to the lawful owner or authorized user, as applicable. Images are used for educational and historical purposes. All feedback welcomed.