Yesterday, I posted my discussion of annual reports of National Breweries Ltd. in Quebec Province in the late 1940s. National Breweries, public-traded and representing all breweries in Quebec outside Molson Brewery, purchased Champlain Brewery of Quebec City, in 1948.

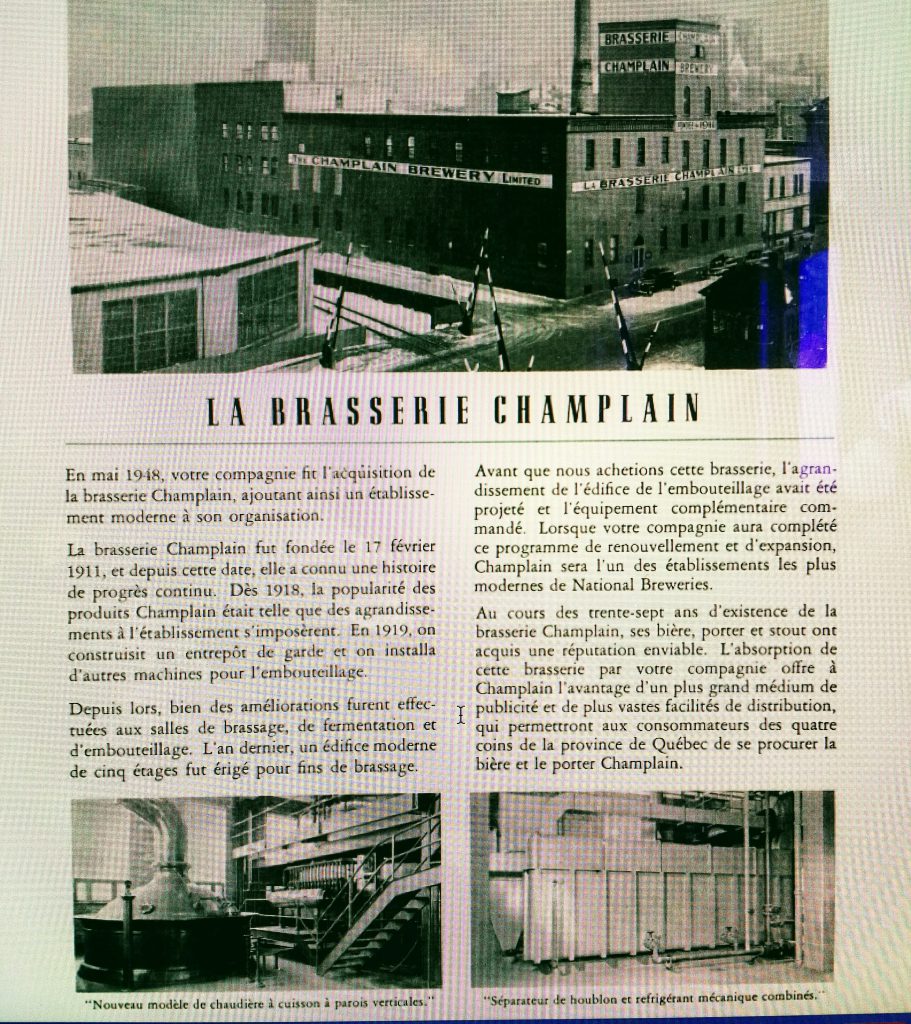

The 1948 annual report stated of the purchase:

(The 1940s annual reports of National Breweries are digitally archived at McGill University’s business library. Most are in English but the 1948 report is in French).

The last paragraph states that following the purchase Champlain will gain greater marketing opportunities – a reference to National Breweries’ comparatively large advertising budget and sales staff. The report continued, “a much larger distribution network … will enable the four corners of Quebec province to purchase Champlain ale and porter”.

So Champlain’s line would reach all of Quebec vs its traditional Quebec City market.

Champlain made India Pale Ale and porter. National Breweries made similar beers at its Dawes, Dow, and Boswell units.

Was National Breweries sincere to maintain the product lines of Champlain? It apparently did so until 1952 when Toronto-based E.P. Taylor’s Canadian Breweries Ltd., took over National Breweries.

Did National fail to realize efficiencies that Taylor was more pitiless to exact from his new purchase? It is hard to say. Either way, the bland, reassuring language in the 1948 report echoes today’s press releases that accompany big brewery buy-outs of craft breweries.

Business does not, in the essentials, change over time. In 1948 National Breweries wanted to convince shareholders and Champlain’s customers that a local hero was better off in National’s fold – even though National Breweries had an existing brewery in Quebec City, Boswell.

Just as today large breweries which buy smaller ones make reassuring noises about maintaining the smaller’s product lines and (often) production capacity (sometimes of course they do, but it is probably the exception).

My sense is National Brewerues would have made the same decisions ultimately as E.P. Taylor did: cut excess production capacity and trim staff, unless a turn-around in profitability and industry prospects came soon.

Clearly, National was in trouble by the early 1950s. Why is hard to say without an in-depth study of Quebec brewing at that time. Even a cursory glance at the annual reports shows, though, the large spike in taxes the industry had to cope with since 1940, imposed to help pay for WW II. It must have kept management up at night.

Ontario-based Edward P. Taylor appeared at the right time, offering a convenient and less risky alternative to an in-house reorganization.

It came at a price, as such deals always do. The still-surviving (1952), separate Dawes Black Horse, Boswell, and Champlain ales disappeared before long, the first two with roots in the early 19th century. Dow Ale was selected as the Quebec champion. The other brands withered although Champlain Porter continued to be produced.

Champlain’s building in Quebec City still exists in modified form, as offices. Canadian Breweries Ltd. after many peregrinations was absorbed into Molson Breweries in 1989.

Molson to this day is run by canny descendants of Lincolnshire-born John Molson. Molson stayed out of the 1909 merger that created National Breweries Ltd. A bruited 1944 marriage of Molson and National Breweries, see Allen Sneath’s book I cited yesterday, came to nought. In retrospect, perhaps a good move by Molson, although perhaps it would have fended off E.P. Taylor Quebec.

Finally, therefore, Molson got it all. In time it made its own compromises, the deal with Colorado’s Coors Brewery about 10 years ago. Still, Molson survives as a substantial Canadian and Canadian-managed business.